At Issue MD - Evictions Are Bad for Business

Evictions Are Bad for Business

Reporting by media outlets often frames the eviction process as a tool utilized by housing providers to increase profit margins. A cursory analysis proves that this framing is factually incorrect. Evictions are expensive for housing providers to pursue and represent a sunken cost that cannot be recovered. Therefore, It’s almost always more cost-effective to work with a good-paying tenant to keep them in place than to repossess the unit through the expensive and time-consuming court process.

Provided below is a quick breakdown of why evictions are bad for business.

Evictions Hurt Housing Providers Too

Housing providers pursuing repossession of apartments see not only legal expenses associated with such a course of action, but also a loss of the revenue stream associated with a particular asset for the duration of the legal process. There is no economic incentive for housing providers to file for repossession of an apartment except as a last resort when a lease has been breached, most often for nonpayment of rent, or for jeopardizing the safety or the quality of life of others at the apartment community. It is unfortunately, however, a necessary part of doing business as housing providers must protect other residents of the community and fulfill financial obligations, including but not limited to maintenance, capital improvements, mortgage payments, utilities, insurance premiums, payroll and taxes, regardless of whether a resident fails to pay rent or fulfill other responsibilities under a lease. And given the soaring costs of providing housing, margins are tighter than ever.

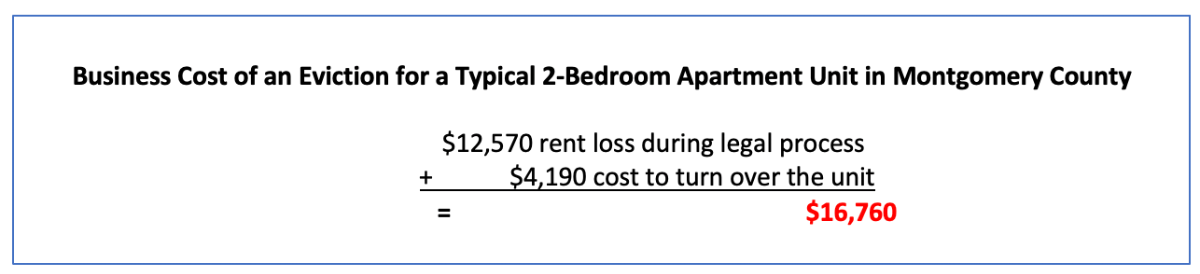

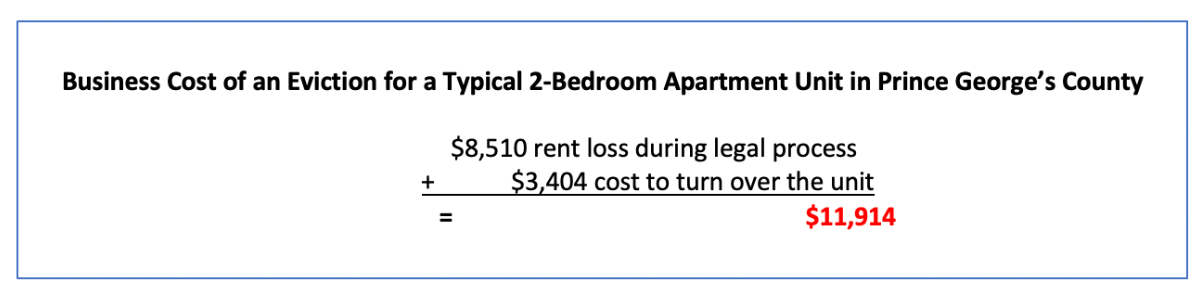

As a general rule of thumb, the cost of turning over a unit is roughly 2-3 month’s rent on top of the rent lost during the legal process. This is attributable to costs for cleaning, repairs, painting, carpet replacement, marketing, new tenant screening and other similar administrative items. (Notably, the industry standard 2-3 month’s rent cost to turnover a unit assumes the immediate turnover of that unit. Current market conditions are favorable, and demand for rental units is high. But a housing provider’s losses can continue to accrue each month that a unit sits vacant).

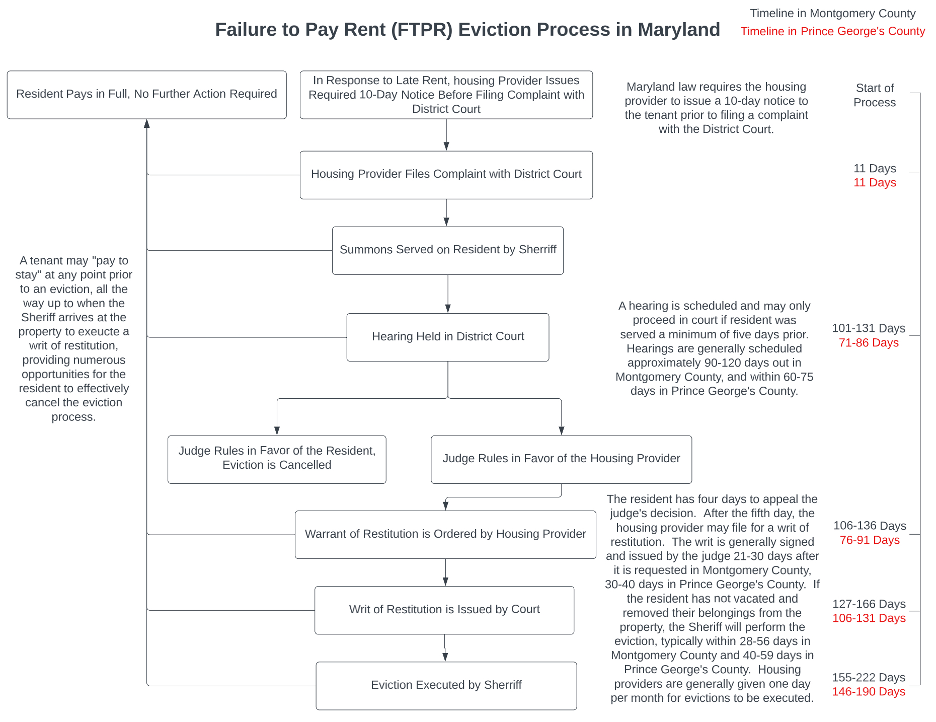

The high cost of repossessing a unit for failure to pay rent is even further exacerbated by the extreme backlog of cases in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties. The legal process is currently running approximately 155-222 days (5-7 months) in Montgomery County and about 146-190 days (5-6 months) in Prince George’s. Add legal costs into the mix and that means that a housing provider is deprived of approximately 60 to 80% of their annual income associated with a particular asset when they are forced to pursue an eviction. Though a housing provider may receive a judgment for rent and other expenses owed in connection with repossessing an apartment, it is often very difficult to collect on such debts and many housing providers choose not to pursue collections, but simply take possession of the unit. (Legal sources cite that fewer than one in five cases see housing providers collect any portion of the debt owed by the tenant). It is important to note that these costs aren’t solely borne by the housing provider, and can contribute to the rising cost of housing for other tenants. This is a powerful motivator for housing providers to work with tenants to keep them in place where there is a reasonable expectation that they can get caught up and meet their financial obligations.

On Average, a Single Eviction Can Cost the Housing Provider in Excess

of $17,000

Take the example of a two-bedroom apartment unit in Montgomery County, renting at a market average rate of $2,095 per month. Optimistically assuming a 155-day timeframe from when the housing provider files with the court to when the eviction is actually executed, that pushes the process to more than five months from start to finish; and, in most cases, a sixth month of unpaid rent. Let’s assume for the purposes of this example that the tenant vacated the unit in relatively good condition with only regular wear and tear and no significant damage to the property. Even at the low end of the spectrum, this equates to approximately two months’ rent required to touch up, market and relet the unit. Even without accounting for legal costs, which can vary widely, the final cost to the housing provider can easily exceed $17,000:

A similar unit in Prince George’s County, rents for a market average rate of $1,702. The eviction timeline, however, runs about 146 days at its most efficient, generally pushing a tenant into a fifth month of delinquent rent. Assuming the same minimal costs for turning over the unit as above, the final cost to the housing provider comes in at approximately $12,000.

Underlying Issues

As established above, housing providers have a built-in financial disincentive to pursue an eviction. The fundamental problem is not greedy or punitive landlords nor is it lazy or ill-meaning tenants/consumers. Rather it is the growing gap between the buying power of lower wages and the fair costs of housing, established like any other service, by rising economic costs and the laws of supply and demand. Nationwide, rent-burdened households are up 29%, now representing more than 30% of American households. Compounding matters, income growth has actually declined by 9% during the same period. That is to say that evictions are a symptom of larger societal issues related to a shortage of affordable housing supply and the failure of incomes to grow consistent with the rising costs of providing housing. This can not be understated in our current economic environment, in which inflation is approaching double digits, driving up the costs of operating rental housing from payroll to building supplies to maintenance and capital costs to taxes and utilities.

It is additionally noteworthy that without action, the projected supply and demand curve will continue to exacerbate affordability issues going forward. As of the most recent census, roughly 878,000 Maryland residents make their homes in approximately 455,500 apartment units throughout the state. According to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Government housing production targets adopted by each county, Montgomery needs to build approximately 4,000 new units per year and Prince George’s needs to build 3,200 new units per year to meet demand. This increased demand is fueled by population growth (an estimated 16.32% increase in the number of households by 2030) and a higher propensity to rent. Corrective action is required or the current housing affordability crisis will only worsen.

As such, an effective long-term approach to reducing evictions must focus on the root causes of affordable housing supply and slow wage growth, particularly among lower income brackets where more than 80% of households are renters and housing cost-burdened. Fortunately, much of the work to identify supply-side solutions has already been done through the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development’s Needs Assessment and 10-Year Strategic Plan. Included within the document is a useful toolbox outlining various approaches to increasing affordable housing supply, including:

- Streamlining regulatory processes that slow and inhibit new investment and development

- Offering operating subsidies for affordable housing developments

- Reducing and eliminating parking requirements

- Creating and increasing funding for housing preservation funds

- Reducing or waiving impact fees

- Offering tax abatements or exceptions for qualified development

- Expediting permitting and approval processes

- Expanding and increasing funding for tenant-based voucher programs

- Increasing the diversity of housing types that can be built by-right

- Expanding access to capital for owners of unsubsidized affordable rental properties

- Expanding emergency rental assistance programs

- Offering density bonuses for qualified development

- Establishing or expanding mixed-use zoning

- Offering programs that fund energy efficiency retrofits

At Issue is compiled by the Apartment and Office Building Association (AOBA) of Metropolitan Washington, and is intended to help inform our elected decision-makers regarding the issues and policies impacting the commercial and multifamily real estate industry.

AOBA is a non-profit trade organization representing the owners and managers of approximately 172 million square feet of office space and over 400,000 apartment units in the Washington metropolitan area. Of that portfolio, approximately 61 million square feet of commercial office space and 151,000 multifamily residential units are located in Montgomery and Prince George’s County, Maryland. Also represented by AOBA are over 200 companies that provide products and services to the real estate industry. AOBA is the local federated chapter of the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International and the National Apartment Association.

Along with input provided by AOBA member companies, the following data sources and references were used in compiling the attached report:

- National Apartment Association’s 2021 Survey of Operating Income & Expenses in Rental Apartment Communities.

- Dees Stribling. “The Race is on Between Multifamily Rental Increases and Inflation.” Bisnow National, December 20, 2021.

- CoStar Commercial Real Estate Data, Information and Analytics Service.

- Consumer Price Index – October 2022. U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. November 10, 2022.

- Apartment and Office Building Association Member Survey on Rent Delinquency, ERAP Program and Court Backlog Experience Survey. March, 2022.

- Evelyn Hodge, Vice President of Operations, eWrit Filings, LLC. Letter to Maryland Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee Chairman William C. Smith, Jr. regarding Court Backlogs on Failure to Pay Rent Cases. February 16, 2022.

- State of the Nation’s Housing Report. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2020 Data.

- National Apartment Association’s We are Apartments Data Set. 2017.

- Region United: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments Planning Framework for 2030. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. March 9, 2022.

- Maryland Housing Needs Assessment & 10-Year Strategic Plan. Prepared by National Center for Smart Growth and Enterprise Community Partners, Inc. for the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development and local partners. December, 2020.

AOBA strives to be an informational resource to our public sector partners. We welcome your inquiries and feedback. For more information, please contact our Senior Vice President of Government Affairs, Brian Gordon.